This month in Illinois State University history: July

From the first day of the University’s 16th president to the impact of a historic heatwave on campus, historian Tom Emery explores this month in Illinois State University history.

July 1

On this date 26 years ago, Victor Boschini took office as the 16th president in the history of Illinois State. Boschini was well-regarded by much of the campus community and alumni base in his four years in the role.

He is also remembered for his never-ending supply of energy and enthusiasm. William Sulaski, the former chair of the Illinois State Board of Trustees, described Boschini’s “energy level” that “is just amazing.” University historian John Freed wrote that “Boschini’s boyish charm and self-deprecating manner won over faculty members.”

Boschini hit the ground running when he came to Illinois State. A Cleveland native, Boschini earned a bachelor’s degree from Mount Union College in 1978.

He then received a M.A. in personnel from Bowling Green State University in 1979, followed by a Ph.D. in higher education administration from Indiana University in 1989. His first official day as Illinois State president was July 1, 1999.

On October 23, 1999, Boschini was formally inaugurated as Illinois State President. The ceremony was the first of its kind at Illinois State since 1968.

Among the many highlights of Boschini’s administration was the adoption of Educating Illinois: An Action Plan for Distinctiveness and Excellence at Illinois State University, 2000-2007. Freed labeled the document as “the university’s blueprint for transforming Illinois State into a ‘Public Ivy.’”

The plan listed the five core values of Illinois State: individualized attention, public opportunity, active pursuit of learning, diversity, and creative response to change. The document is considered a landmark in the history of Illinois State.

Under Boschini’s direction, Illinois State embarked on its first capital campaign, “Redefining Normal,” with a goal of raising $88 million. The public phase of the plan opened on March 22, 2002, with speaking appearances by the late Madeleine Albright, a former U.S. Secretary of State, and Donald McHenry, a member of the Illinois State class of 1957 who was the ambassador to the United Nations under President Jimmy Carter. “Redefining Normal” closed on December 31, 2004, with a total of just over $96 million.

Four endowed chairs were received through the campaign, as well as 154 endowed scholarships. The University’s endowment increased by 70% during the campaign.

Two days after the attacks of September 11, 2001, Boschini spoke at a student-organized rally on the Illinois State Quad in front of 10,000 students, faculty, and staff, many of them waving American flags. Along with Provost Alvin Goldfarb, Boschini urged the crowd not to let anger turn into intolerance.

Buckets were passed among the crowd, and $25,000 was collected for the United Way of New York September 11 Fund within an hour. Boschini later called the rally his favorite event in his time at Illinois State.

With Boschini in charge, the academic reputation of Illinois State, already strong, continued to improve.

Boschini also directed money to be used for a new-look alumni magazine, a full-color, slick-paper format that provided a host of upgrades to the publication. He also spearheaded massive improvements to the “town and gown” relationship of the University to the surrounding areas.

He was praised by Freed for his “excellent rapport with students” and “a cooperative rather than a confrontational relationship between the administration and faculty.”

On January 30, 2003, Illinois State announced that Boschini was leaving to become chancellor of Texas Christian University. Freed wrote that “both the university and the community as a whole felt a genuine sense of loss” at the news. Boschini’s last day as Illinois State president was June 1, 2003.

In a 2006 interview, Boschini said that he missed “tons of things about Illinois State and Normal … like walking in the Quad.” He added that he would love Reggie Redbird, the Illinois State mascot, “for life.”

Many members of the Illinois State community feel the same way about Vic Boschini, whose boundless energy, foresight, and people skills transformed the campus to meet the 21st century.

July 4

Today is the Fourth of July, which normally falls when Illinois State is out of regular session. Summer school is still going on, though, and there’s plenty of activity on campus, even in past eras.

On July 4, 1876, the nation was in the midst of its 100th anniversary commemorations, which also had meaning in Normal. That day, the students and faculty planted a “Centennial elm” in honor of the occasion.

Adding to the significance was a box that was buried under the roots of the tree as a sort of time capsule, with documents, papers, and other memorabilia. Illinois State President Richard Edwards delivered a speech at the tree for the event.

The campus celebrated the Fourth in 1905 by interrupting a period of class study for one student’s “reading of portions of the Declaration of Independence.” The Vidette published a regular issue on July 4, 1913, highlighting that year’s summer school.

In 1917, the University looked forward to a July 4 performance by the Coburns, an outdoor acting ensemble that toured the Midwest. As The Vidette reported, “their repertory for 1917 consists of four plays: The Yellow Jacket, Julius Caesar, Romeo and Juliet, (and) Much Ado About Nothing.”

The next year, the United States had joined World War I, and Illinois State men and women were part of the effort. From his camp hospital in France, Pvt. J. Willis McMurray wrote home on the Fourth of July. The Vidette wrote that “he described the Fourth as celebrated in France, and even in the hospitals.”

The rigors of academia on the Normal campus, though, did not interfere with the holiday in 1922. A notice in The Vidette advised students that “the library will close for the exercises” on July 4. When they are over it is to be opened for a short time to circulate books, and then will be closed at noon for the rest of the day and evening.”

Certainly, Illinois State students could have used the break. There was also a day off in 1924, as the summer school did not hold session on July 4.

In 1926, the nation celebrated its 150th anniversary, and The Vidette paid tribute in an editorial that discussed the massive celebrations in the city of Philadelphia, where the Declaration of Independence was signed. The paper honored “the courageous souls who fought for [the Declaration, who] prepared the way for us … our right to the free expression of living and the promise of civilized progress.”

Patriotism and accuracy were the subjects of an address at a General Assembly on campus on July 7, 1930. There, Charles A. Harper, an associate professor of history at Illinois State, asked, “what really happened on July 4, 1776?” He continued with a discussion about, as The Vidette wrote, “the confusion about the events” of that momentous day.

Three days earlier, Illinois State students celebrated the weekend of the Fourth with a bus trip to Chicago. They were a dedicated group; the bus left Normal at 2:30 a.m. on July 4. The party then spent two nights in the city, visiting the Art Institute, Field Museum, Shedd Aquarium, and several parks.

The country was at war again in 1942, and the students and faculty of Illinois State saw a deeper meaning to the holiday. The Vidette asked various members of the campus community for their thoughts, which ranged from patriotism to fear.

M. Regina Connell, an assistant professor of Latin, believed that “1776 has more significance than ever before in view of the struggle we are in,” while student Ruth Croxen solemnly declared, “we might not have the Fourth next year.”

C.F. Malberg, an associate professor of psychology, thought that the “Fourth this year ought to be an occasion for the intensifying of our patriotic efforts toward winning this war.”

Some missed the familiar faces of friends and relatives. Student Edith Babington said, “there are a lot of soldiers around here who will not be home for the Fourth,” while student Andy Young expressed his “deep sympathy for fellow classmates engaged in the present war.” Home economics student Dorothy Catlin lamented, “It’s going to be kinda funny without my brother around.”

Three years later, the nation was headed for happier times on July 4. That day in the Chicago suburb of Mundelein, two former Illinois State students wed in a local rectory. The bride, Phyllis Oko, was a 1944 Illinois State graduate, while the groom, Army Sgt. Lawrence Rouse, was from the class of 1943.

Sgt. Rouse was the brother of Marian Rouse, the business manager of The Vidette the previous year and the incoming president of the Student Council. They were among the many Illinois State graduates who looked forward to the joy and revelry of July 4 holidays in peacetime.

July 7

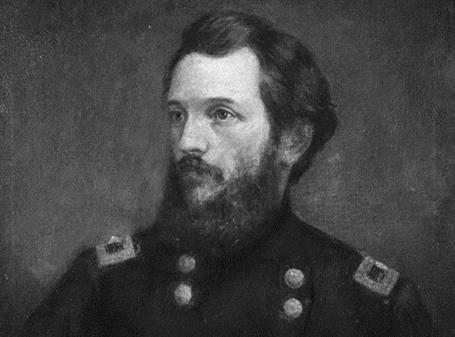

On this date in 1862, Illinois State students were heavily involved in the Civil War battle of Cache River, Arkansas, as part of the 33rd Illinois, which was forever known as the “Teacher’s Regiment.”

The first colonel of the 33rd was Charles Hovey, the founding president of Illinois State, who distinguished himself for bravery and valor in the battle.

Clearly, the men of the 33rd were not just bookworms; they were hardened fighters. Their toughness was on display in the fight at Cache River as Confederates looked to slow the Union Army of the Southwest in their advance on eastern Arkansas.

Hovey led a brigade that included the 33rd across the river when two Texas cavalry regiments tried to stop the crossing. Thus began the small, but spirited, battle of Cache River, which is also known by several other names, including Cotton Plant, Hill’s Plantation, and Round Hill.

The Federals were initially overrun, but Hovey stabilized the situation quickly. In 1993, Trans-Mississippi theater historian William Shea wrote that “in a moment of inspiration, Hovey dismounted and picked up a rifle and cartridge box from a wounded soldier. He walked forward a few yards, found an unoccupied tree, and methodically began to load and fire in the general direction of the enemy.”

Hovey managed to fire two or three rounds before he was struck in the chest by a spent bullet. His sturdy nature, however, came through. Shea wrote that Hovey “picked up the bullet and shouted above the din that the rebellion ‘did not seem to have much force in it.’”

Shea summarized that “the colonel’s bravura performance had an ‘electric effect’ on the men around him.”

Civil War battlefields were no place for the faint of heart, even in smaller battles like Cache River. One officer of the 33rd wrote that “a few feet above our heads the trees were almost swept clean” by flying bullets. He continued that “leaves and twigs and limbs severed from the trees by the leaden storm dropped upon us like hail.”

Hovey later halted a retreat from his troops by dramatically jumping a fence on his horse with a sword in hand, screaming, “Lord Almighty God, boys! Are you going to run like sheep?” Shea declared that, “for the second time in an hour, the former college president saved the day.” Hovey would later ascend to brigadier general.

In one instance, Sgt. Harvey Dutton, a Normal student in Company A, was threatened by a rebel horseman. Dutton had just fired his musket, and was largely helpless; in that era, most weaponry was single-shot, and even the best soldiers could reload only three times a minute.

Dutton had no way out, and didn’t even try. Rather, he reached for a revolver from his belt and dropped the enemy horseman. Dutton survived the war and lived to a ripe old age, dying in 1928 at the age of 92.

The tide of the battle soon switched from retreat to advance, which carried the fight for the Union. Shea reports that the Illinoisans “loosed a smashing volley at point-blank range against the flank of the Confederate column. The ‘storm of lead’ practically annihilated the leading elements of the 12th Texas Cavalry, ‘tumbling horse and rider indiscriminately over each other.’” Hovey proudly wrote “they left as suddenly as they came and in great disorder.”

That largely ended the battle, but one Normal University man, Edward Pike of Company A, earned the highest recognition of all.

Pike displayed his devotion at Cache River as he prevented a cannon from falling into enemy hands amid a galling fire. Though the gun weighed 2,000 pounds, the slender Pike began dragging the piece to the rear as another man of Company A, Chauncey Chamberlain, stepped forward to help amid pistol and shotgun fire from enemy Texans.

Shea’s 1993 account marvels that the fire “somehow failed to hit either man” before the rest of Company A fought back and repulsed the rebels with “a flurry of rifle fire. Making the most of this brief respite, Pike and Chamberlain manhandled the cannon out of the enemy’s grasp and attached it to the limber” before it was hauled to safety.

Though he was unharmed, Pike’s cap was pierced by a bullet during the struggle. His valor earned him the Medal of Honor, the highest decoration for military service.

July 15

On this date in 1936, the high temperature in Bloomington-Normal reached 114 degrees, the warmest ever recorded in the Twin Cities. Like everyone else in the area, Illinois State students were sweltering.

Illinois and much of the Midwest endured unseasonably hot summers for much of the 1930s. Nothing, though, was as brutal as the summer of 1936, when much of the nation was trapped in overpowering heat as Americans struggled to recover from the Depression.

At least 13 states from New Jersey to Louisiana recorded their warmest-ever temperatures during the summer of 1936. An estimated 4,500 to 5,000 deaths nationwide were attributed to the heat that year.

In Illinois, Peoria residents suffered through 23 days of 100 or better that summer, while Springfield reached 100 degrees on 29 days that summer. Highs in the capital city never dipped below 100 from August 12-28—a span of 17 days.

Fifty people died from heat-related causes in Springfield in 1936. To the north in Moline, the mercury hit 100 or above for 11-straight days from July 5-15.

In that same span, high temperatures in Bloomington-Normal reached at least 106 degrees. Five of the six hottest days on record in the Twin Cities occurred consecutively from July 11-15, 1936. The highs, respectively, in that stretch were 109, 110, 109, 111, and 114 degrees.

Like everyone else, Illinois State students were hammered by the hot temperatures. On July 16, the university physician told The Vidette that “the heat wave is the chief cause of the most of our present illnesses” on campus. She reported “an increased number of cases of fainting,” adding that “boils, and skin and ear infections are prevalent, all of which are probably caused by bathing in impure pools.”

Sunburn, however, was not a problem. The doctor attributed that “to the fact that the extreme heat drives the students to the shadiest places available.”

Finding that shade was a problem, as Illinois State students scrambled to find anywhere that offered some relief. On July 30, The Vidette reported that the fire escape in the rear of Fell Hall was “much used as a heat escape” by students who wanted “a shady vantage point from which to woo any transient breeze that may chance that way.” In that same issue, the paper lamented heat so severe that it “would not let one sleep.”

The intramural programs for the summer school term were hit particularly hard, as many students dropped out or didn’t show up. On July 9, The Vidette reported that “forfeit games mar [the] third week of intramural play.” No games in IM volleyball were played that week “because of the tropical temperature of the gym.”

A week later, the paper followed up that “the intense heat…seems to have put a crimp in the more active sports of the intramural program. Most of the games this last week were won on forfeits.” Still, at least 40% of male students participated in the IMs. The director stated that “when one considers the extreme heat of most of the term, this [was] a commendable turnout.”

Later generations of Illinois State students were able to take advantage of an invention that their peers would have craved in 1936: air conditioning. But the unfortunate souls who sweltered on campus, and around the nation, in 1936 had little respite in one of the worst summers on record in American history.

July 20

On this date in 1969, Apollo 11 landed on the moon. With an estimated 650 million watching worldwide, including many at Illinois State, the lunar module landed at 3:17 p.m. Normal time on July 20.

Neil Armstrong finally stepped out of the module at 9:39 p.m., and made his famous first step at 9:56 p.m. He was followed by fellow crew member Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin 19 minutes later. They were the first of 12 men, all Americans, to walk on the lunar surface between 1969-72.

Aldrin and Armstrong were on the moon for a total of 21 hours, 36 minutes, with 2 hours, 31 minutes spent outside the lunar module.

The Vidette recognized the achievement of the first lunar landing on July 23, 1969, with a headline comprised of the simple, yet respectful, words “Congratulations Apollo 11 Astronauts.”

In his column in that issue, Ed Pyne, who went on to a long career in local journalism, called the landing “the greatest day” as Armstrong and Aldrin “joyously bounced up and down on the moon’s surface,” sending back “unbelievably fabulous pictures.”

One of the moon rocks that Armstrong and Aldrin collected on the lunar surface was later displayed at Illinois State. The stone, which was loaned from a NASA station in Cleveland, was the highlight of a three-day “re-opening” event at the Funk Gem and Mineral Museum in Cook Hall on April 27-29, 1973.

As expected, security for the moon rock was tight. The Vidette reported that the stone “will be under an official guard while it is on campus.”

Illinois State students and faculty had watched the space race with keen interest throughout the decade, with a mixture of awe, inspiration, and fear. That was certainly the case in The Vidette edition of May 10, 1961, which was published five days after Alan Shepard had become the first astronaut in space.

In a 15-minute flight, Shepard and Mercury-Redstone 3 were shot straight up into space in an effort to keep up with the Soviets, who had been the first to orbit the Earth the previous month.

The Vidette was inspired by Shepard’s feat, imploring fellow Americans to say, “Yes, we did it! We couldn’t be happier.” The paper, though, feared that the United States would lose the space race, noting that the accomplishment “means very little compared to [the Soviets’] around the world orbit.”

“This is just the beginning for us,” concluded The Vidette, though the concern was evident. “America must rise yet further. She will not fail; she cannot fail.”

On February 20, 1962, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth, circling three times. The accomplishment had personal meaning for Dr. Eric Smithner, an associate professor of foreign languages at Illinois State, who had been a classmate of Glenn at Muskingum College in Ohio.

The Vidette reported that Smithner “remembers John Glenn as a red-haired, freckle-faced kid whom the girls thought of as cute.”

That May 1, The Vidette used Glenn’s feat to call on everyday improvements back on Earth. “It seems ridiculous,” wrote the paper, “that John Glenn can circle the Earth three times … yet thousands of Americans cannot travel more than a few miles on our highways without being killed in the process.” The paper backed up its statement with some eye-opening statistics on the number of passenger and pedestrian deaths in the U.S.

On March 14, 1966, Illinois State space buffs could enjoy a lecture at Bloomington Senior High School from Dr. Leonard Reiffel, who directed a program for NASA’s Lunar and Planetary Programs Office. His topic was “Our Space Program: How Valid?”

On April 10, 1970, The Vidette printed a wire report on Apollo 13, “a rundown of America’s third moon landing in nine months.” Apollo 13, though, never reached the lunar surface after an explosion that threatened the lives of the astronauts on board, and gripped Americans with fear that the three men may not return.

One of the Apollo 13 astronauts, James Lovell, later had Illinois State on his mind, at least indirectly. In early 1972, the Illinois Board of Higher Education called for the cut of all mandatory physical education requirements at six state universities, including Illinois State.

Lovell, then-head of the President’s Council on Fitness, joined Governor Richard Ogilvie, the American Medical Association, and various presidents and deans in penning a letter to President Richard Nixon condemning the actions of the ISBE.

Illinois State continued its fascination of the space race right into the final two lunar missions, Apollo 16 and Apollo 17. On April 27, 1972, the words “Apollo 16 splashes down today” were found next to the masthead of The Vidette.

That December 13, The Vidette covered Apollo 17 under the headline “Apollo explorers enjoy lunar scene.” Back on Earth, the Illinois State community, watching the video feeds, enjoyed it themselves, as they had throughout all six American lunar landings.

Tom Emery is a freelance writer and historical researcher who, in collaboration with Carl Kasten ’66, co-authored the 2020 book Abraham Lincoln and the Heritage of Illinois State University.

Latest Campus News

- Beyond the headlines: Stephanie Rodriguez ’18 connects with communities through bilingual reportingStephanie Rodriguez ’18 never imagined her journalism career would take her from reporting on a dramatic murder trial featured on the true crime show 48 Hours to covering alligator mating season in Florida. Only seven years in, she's earned an Emmy nomination, worked in four television markets, and has became a voice for those who often go unheard.

- Video: Blooming for 20 years: Horticulture Center welcomes community for annual Autumnal FestivalFrom volunteers to students, the people behind ISU’s Horticulture Center are preparing to mark its 20th anniversary during the Autumnal Festival.

- Our newest Redbirds by the numbers: Fall 2025Nearly 6,000 new Redbirds are on campus this fall, as Illinois State University continues the trend of attracting strong classes of high-achieving students.

- Rittenhouse-to-Sobkowicz connection key for No. 7-ranked Redbird football teamWhen the Redbirds (0-1) take the field this weekend for the football season home opener against Morehead State (1-0) on Saturday, September 6 at 6 p.m. at Hancock Stadium, they will bring along with them the experience of playing the storied Oklahoma Sooners one week ago.

- Growth abroad: Illinois State students reflect on life-changing experiences in Kenya and South AfricaNot only did Illinois State students Makenna Williams and Avery Pierre deepen their understanding of the world while studying and serving abroad in Africa this summer, but they also returned home with a clearer sense of purpose.

- Our Newest Redbirds: Transfer student brings creative spirit, sense of community to his new schoolDevin Briseno hopes to carve out a career as a filmmaker, but first he must complete the important role of being a college student. A transfer student, he has just begun his sophomore year at Illinois State University.